- “Twelve shattered myths:

- It takes a great idea to start a great company: Like the parable of the tortoise and the hare, visionary companies get off to t a slow start but often win the long race. Some visionary companies started without any specific idea. They were significantly less likely to have early entrepreneurial success than the comparison companies.

- Visionary companies require charismatic and great leaders. CEOs of visionary companies focused not on being time-tellers but rather on building clocks.

- Visionary companies exist to make profit/maximize shareholder returns: While making money and turning a profit is as important to them as blood and water is to life, it is not the end goal. They have a core ideology – core values and sense of purpose beyond just making money.

-

- There needs to be a “correct” set of values. Visionary companies do not ask “what should we value” instead they ask: “what do we actually value deep down to our toes?”. The crucial variable is not the content of a company’s ideology but rather how deeply it believes its ideology, and how consistently it lives, breaths, and expresses it in all that it does. These values do not need to be humanistic or enlightened although they often are.

- The only constant is change: Visionary companies almost religiously preserve its core ideology. Core values in a visionary company form a rock-solid foundation and do not drift with the trends and fashions of the day. The basic purpose a visionary company – its reason for being, can serve as a guiding beacon for centuries, like an enduring star on the horizon. Yet, visionary companies display a capacity for change and progress that does not compromise their cherished core ideals.

- blue-chip companies play it safe: In reality, these visionary companies do not hesitate from pursuing Big, Hairy and Audacious Goals. Visionary companies judiciously used BHAGs to stimulate progress and blast past the comparison companies at crucial points in history.

- Visionary companies are a great place to work for everyone: in reality, visionary companies are only great for those whose values are congruent with the values of the company. There is no middle ground- you’ll either flourish or fail.

- Visionary companies achieve their success by complex and strategic planning. To the contrary, these companies achieve their success by experimentation, trial and error, opportunistic, and accident. They do a lot of “let’s try a lot of stuff and keep what works”. This resembles the principle of evolution Darwin described in his book.

- Visionary companies focused on hiring external CEOs to bring about significant change. That was rarely the case.

- Visionary companies focus primarily on beating competition: They focus instead of finding what it is that they can the best in the world at, where their passion is, and the biggest driver for profit. On top of that, they overlay that with pursuing BHAGs that lie at the intersection of passion, being the best in the world and being the most impactful factor in driving results.

- Visionary companies became visionary after developing a vision statement: in reality, the vision statement was one of a thousand steps in expressing the fundamental characteristics of a great company.

- You can’t have your cake and eat it too. Visionary comapnies are not constrained by OR. they always think AND.

- A visionary CEO is one who does not just have the ability to tell everyone what time it is, but makes a clock so that other people can tell the exact time too. Their primary output is not the tangible implementation of a great idea, the expression of a charismatic personality, the gratification of their ego, or the accumulation of their personal wealth. Their greatest creation is the company itself and what it stands for.

- Business schools teach the concept that in order to start a successful business, you’ll need to first come up with a product and a target market for it, and move to fulfill the demand before the demand is gone. Research that Jim did shows that this was rarely the case for visionary companies. The company wasn’t the vehicle for products, the products were the vehicle for the company. Focusing on the product will shift your focus away as an entrepreneur from where it should be: the foundation of a company.

- Take for example Westinghouse vs GE: the founder of Westinghouse had founded some 50+ businesses before creating Westinghouse the company. Also he placed a bet on the AC current vs the DC current that Edison had at GE. Westinghouse was ahead of GE at the time. The president of GE did not come up with any insights similar to Westinghouse’s CEO, but he created an innovation lab at GE. Westinghouse’s CEO told the time. GE’s created a clock.

- Another example is Sam Walton of Walmart. He did not preach change, the need to continuously improve and experimentations. Rather, he built structure and process in places to make the organization more receptive and susceptible to change and continuous improvements. He made it easy for for employees to bring up ideas to save costs or improve customer experience. Employees were rewarded for it through profit sharing and stock options. He also made it easier for these ideas to propagate across the vast organization.

- If you are involved in building and managing a company, it is best to think about building the characteristics of a visoinary company and of you being an orgnaizational visionary as opposed to being a product visionary or seeking the personlaity characteristics of charistmatic leadership.

This requires a shift in perspective similar to the shift occurred with the Newtonian and Darwinian revolutions.

Prior to the Newtonian revolution, people thought of events as act of God. If a child broke his leg, that was an act of God. If drought occurred, it was an act of God too. However, the Newtonian school of thinking rejected that explanation and said that God sat the principles as to how the universe works. Discovering these principles allowed us to better determine cause and effect of events.

Similarly, prior to the theory of evolution, the thought was that God created each species on its own and for its own purpose. The theory of evolution discovered the underlying process of evolution – genetic code, DNA mutation and variation, and natural selection. The beauty and functionality of the natural world springs from the success of its underlying processes and intricate mechanisms in a marvelous “ticking clock”. - Prior to the American revolution in 1787, countries’ success were determined by how effective their leadership – typically the king, was. With the founding of the United States, the critical question at the constitutional convention was not “Who is the best president? who should lead us? who is the wisest?” but rather how to build a process that will give us good presidents long after we’re dead and gone? what type of country do we want to build? on what principles?

- “For now, the important thing to keep in mind is that once you make the shift from time telling to clock building, most of what’s required to build a visionary company can be learned. You don’t have to sit around waiting until you’re lucky enough to have a great idea. You don’t have to accept the false view that until your company has a charismatic visionary leader, it cannot become a visionary company. There is no mysterious quality or elusive magic. Indeed, once you learn the essentials, you—and all those around you—can just get down to the hard work of making your company a visionary company.”

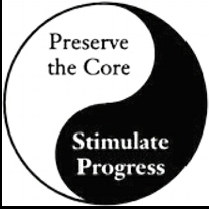

- One of the hallmarks of a visionary organization is the ability to hold simultaneously two seemingly contradicting principles and yet fulfill each of these principles effectively. Think of an organization that values core operating principles AND still allows for innovation and creativity, an organization the focuses on shareholder profit AND doing good in the world.

The key idea here is that these organizations do not seek balance between both seemingly contradicting ideas. Instead: you do both to an extreme. To give an analogy of a yin-yang symbol from Chinese dualistic philosophy: you don’t blend the yin and yang into a gray. Instead you aim to be yin and yang distinctly all at the same time.

“Irrational? Perhaps. Rare? Yes. Difficult? Absolutely. But as F. Scott Fitzgerald pointed out, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”1 This is exactly what the visionary companies are able to do.” - It is important to be a clock-builder with a human side. GM’s previous CEO Alfred Sloan was an excellent clock builder: he built the processes necessary for GM to be profitable, and to compete sustainably. He wrote a memoir that was highly impersonal: managing of a business so it can produce effectively, provide jobs, create market and sales and generate profits. Business in the community, business as a life rather than a livelihood, business as a neighbor and as a power center – these were all absent in Sloan’s world.

- One of the clearest differences between visionary and non-visionary companies is that visionary companies had an ideological underpinning in their pursuit and were less driven by profit. That is not to say that profit was not important to them. Rather, they purse their aims profitably. Profit is like blood and water: necessary to sustain life but aren’t the point of the life or the end in itself.

- Johnson and Johnson operated based on the philosophy that it had a duty first and foremost towards the consumers of its products – highest quality, most effective and reasonably priced and safe products. Then, it had a duty towards its employees – promote career advancement, respect, work with a purpose, fair pay, and excellent work conditions. It had the duty of hiring the best exectuvies that drove the company in the right direction. It had the duty of being a good corporate citizen – do good by the community, environment and all stakeholder. Finally, it had a duty towards shareholders – note how shareholders ranked last in the list.

- There is no specific ideology that is essential to a company becoming a visionary company. It is more the authenticity of the ideology and the context to which a company attains consistent alignment with the ideology counts more than the content of the ideology.

- It doesn’t matter whether you agree with Philip Morris ideology. It doesn’t matter whether a company has a “likable” core ideology but whether it has a core ideology that gives guidance and inspiration to people inside that company.

- Visionary companies do not treat ideologies as words. They turn it into a reference points that guides every single decision made. They do that by sharing these ideologies with the outside world, which increases the likelihood and level of commitment to them, and also they take steps to make the ideology pervasive throughout the organization and transcend individual leaders.

- In fact, they promote people based on how much their actions align with the ideologies of the company.

- They indoctrinate employees into a core ideology, creating cultures so strong that they are almost cult-like around the ideology.

- There will always be a difficulty in living with the tension between pragmatism and idealism, or what Jack Welsh calls “numbers and values”

“Numbers and values. We don’t have the final answer here—at least I don’t. People who make the numbers and share our values go onward and upward. People who miss the numbers and share our values get a second chance. People with no values and no numbers—easy call. The problem is with those who make the numbers but don’t share the values…. We try to persuade them; we wrestle with them; we agonize over these people.“ - Core Ideology = Core Values + Purpose

- Core Values: Enduring and Essential guidelines that control what decisions are made and how; not to be compromised for short-term expediency or financial gain, not to be confused with specific cultural and operating practices.When setting core values, it is important that these values are authentic rather than they be copies of someone else’s values. They don’t need external justification nor do they change with a changing environment. Examples include the following:

- Open-mindedness and curiosity: every human should be afforded an opportunity to explain their point of view

- Maintaining excellent health at all times

- Doing good by those who have done good towards us.

- Purpsoe: why an organization exists beyond making money. Perpetual guiding start on the horizon. It is fundamental, enduring and broad.

- Something enduring and long-lasting after you’re gone.

- “Hewlett, Packard, Merck, Johnson, and Watson didn’t sit down and ask “What business values would maximize our wealth?” or “What philosophy would look nice printed on glossy paper?” or “What beliefs would please the financial community?” No! They articulated what was inside them—what was in their gut, what was bone deep. It was as natural to them as breathing. It’s not what they believed as much as how deeply they believed it (and how consistently their organizations lived it). Again, the key word is authenticity. No artificial flavors. No added sweeteners. Just 100 percent genuine authenticity.”

- Companies can get in trouble when they confuse core ideology with specific, noncore practices. They confused the core ideology with a manifestation of its core ideology. The manifestations must be open for change. Examples:

- HP’s core ideology is to recognize that its most important asset is its employees. A manifestation of this was to bring everyone coffee and doughnut at 10am. This can change.

- Walmart’s commitment to “exceed customer expectations” is a core ideology. A manifestation of it is to have an employee greet customers at the door.

- 3M’s “respect for individual initiatives” is a permanent, unchanging part of its core ideology; the 15 percent rule where employees get to spend 15% of their time on initiatives of their ownis a noncore practice that can change.

- It is absolutely essential not to confuse core ideology with culture, strategy, tactics, operations, policies and other noncore practices. over time, culture norms may change, strategy, product lines, and goals must.

- The central concept of the book: preserve the core and stimulate progress:

- The single most important takeaway of this book is the importance of building tangible mechanisms that preserve the core ideology and stimulate progress. This is the essence of clock building.

- Core Values: Enduring and Essential guidelines that control what decisions are made and how; not to be compromised for short-term expediency or financial gain, not to be confused with specific cultural and operating practices.When setting core values, it is important that these values are authentic rather than they be copies of someone else’s values. They don’t need external justification nor do they change with a changing environment. Examples include the following:

- To stimulate progress, you need Big Hairy Audacious Goals. The essential point of a BHAG is better captured in questions such as “Does it get people’s creative juices flowing?”, “do they find it stimulating, exciting and adventurous?” “Does it stimulate progress, does it create momentum? does it get people going?”

- “THE BHAGs looked more audacious to outsiders than to insiders. The visionary companies didn’t see their audacity as taunting the gods. It simply never occurred to them that they couldn’t do what they set out to do”

- “In grooming his son for the CEO job, he continually emphasized the importance of “keeping the company moving” and that vigorous movement in any direction is better than sitting still; always have something to shoot for, he advised.”

- ““VISIONARY,” we learned, does not mean soft and undisciplined. Quite the contrary. Because the visionary companies have such clarity about who they are, what they’re all about, and what they’re trying to achieve, they tend to not have much room for people unwilling or unsuited to their demanding standards.”

- There are four characteristics of cults at visionary companies:

-

- Fervently held core ideology = core values + purpose.

- indoctrination

- tightness of fit

- Elitism

-

- “Please don’t misunderstand our point here. We’re not saying that visionary companies are cults. We’re saying that they are more cult-like, without actually being cults. The terms “cultism” and “cult-like” can conjure up a variety of negative images and connotations; they are much stronger words than “culture.” But to merely say that visionary companies have a culture tells us nothing new or interesting. All companies have a culture! We observed something much stronger than just “culture” at work. “Cultism” and “cult-like” are descriptive—not pejorative or prescriptive—terms to capture a set of practices that we saw more consistently in the visionary companies than the comparison companies. We’re saying that these characteristics play a key role in preserving the core ideology.”

- “It is important to understand that, unlike many religious sects or social movements which often revolve around a charismatic cult leader (a “cult of personality”), visionary companies tend to be cult-like around their ideologies.”

- “Companies seeking an “empowered” or decentralized work environment should first and foremost impose a tight ideology, screen and indoctrinate people into that ideology, eject the viruses, and give those who remain the tremendous sense of responsibility that comes with membership in an elite organization. It means getting the right actors on the stage, putting them in the right frame of mind, and then giving them the freedom to ad lib as they see fit. It means, in short, understanding that cult-like tightness around an ideology actually enables a company to turn people loose to experiment, change, adapt, and—above all—to act”

- Progress is stimulated by BHAGs and is also stimulated by tinkering: many small experiments that do not cost a lot. Whichever ones prove successful, you latch on to and grow. It is exactly how evolution works: if you look at how different creatures have adopted so successfully to their environment, you might think that they were pre-designed and created to exactly fit that environment. In reality though, the work of Charles Darwin revealed that it is through a process of random mutations in the genetic pool, nature ended up having different versions of capabilities and features for the same species. Those with the capabilities and features that best suited the environment remained, thus expanding their ratio in the genetic pool as those with other variations perished. So it is an unplanned progress.

“multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die” - “It might be far more satisfactory to look at well-adapted visionary companies not primarily as the result of brilliant foresight and strategic planning, but largely as consequences of a basic process—namely, try a lot of experiments, seize opportunities, keep those that work well (consistent with the core ideology), and fix or discard those that don’t”

- There is not a wholesale analogy between biological evolution and evolution of organizations.

- Evolution in species happen unconsciously, but in organizations it requires conscious selection.

- Companies have the ability to set goals and plans. you use BHAGs to define a mountain to climb, and use evolution to invent a way to the top.

- “During our interview with Bill Hewlett of HP, we asked him if there is any company that he greatly admired and saw as a role model. He responded without hesitation: “3M! No doubt about it. You never know what they’re going to come up with next. The beauty of it is that they probably don’t know what they’re going to come up with next, either. But even though you can never predict what exactly the company will do, you know that it will continue to be successful.”“

- Using 3M as a blueprint for evolutionary progress at its best, here are 5 basic lessons from stimulating evolutionary progress in a visionary company:

- Experiment: do something. do not stay still. Vary, change, try something new consistent with the core ideology even if you can’t predict precisely how things will turn out.

- Failure has to happen. It is an integral part of the evolutionary process and a sign that you are trying to evolve by building new branches. You cannot tell ahead of time which variations will be favorable. Failure that is not catastrophic is an essential component of evolution. It is critical that you do not discourage failure.

- Take small steps: of course it is easier to tolerate failed experiments when they are just that: experiments, not massive corporate failures.

- Let employees run with their own ideas: your task is to make sure that there are great people on the bus and then do not impose a lot of structure on how they stick to the core ideology = core values + purpose.

- Very important: make sure that as a manager, you don’t just voice the principle of evolutionary progress, but rather that you institutionalize tangible plans to create an environment that nurtures that evolution.

- Award it: Recognize employees’ efforts when it comes to attempting evolutionary progress.

- What not to do:

- Obsessively control how people do work.

- Adopt a top-down approach when it comes to generation of new ideas

- do not create a rift between employees at the bottom of the org chart and managers and execs at the top.

- Stay close to the knit: this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t evolve. You can stay close to the core ideology but everything else is malleable.

- The critical question is: “how can we do better tomorrow than we did today?”. Institutionalize this question as a way of life – a habit of mind and action.

- Visionary companies attain their extraordinary position not because of their superior insights or special secrets of success, but largely because of the simple fact that they are so demanding of themselves.

- “Discipline is the greatest thing in the world. Where there is no discipline, there is no character. And without character, there is no progress. . . . Adversity gives us opportunities to grow. And we usually get what we work for. If we have problems and overcome them, we grow tall in character, and the qualities that bring success.”

- “COMFORT is not the objective in a visionary company. Indeed, visionary companies install powerful mechanisms to create discomfort—to obliterate complacency—and thereby stimulate change and improvement before the external world demands it.”

- Strategies to prevent complacency from becoming the norm:

- Challenge your own self: PG did that by having different departments compete against each other

- Cut off revenues from mature products – Motorola discontinued selling mature products that accounted for significant sales volume, and Merck consciously tapered off sales from medicines that were becoming commoditized

- HP had its managers rank team members against each other across teams to force an uncomfortable discussion around excellence

- Walmart compared sales of the day of the year to the same day last year and demanded that sales figures grow.

- Do no accept a trade-off between short-term performance and long-term goals. You set goals first and foremost for the long term while simultaneously holding yourself to highly demanding short-term standards.

- Questions to consider as a manger in a company or as you build a company:

- What mechanisms will you create to obliterate complacency and maintain a state of discomfort and continuous daily improvement?

- How will shift from a mindset of an ultimate goal that once reached you can coast to an always-on improvement mode where you’ll never reach a destination but you’ll continually improve?

- What are you doing to invest for the future while doing well today? Does your company adopt innovative methods and technologies before the rest of the industry?

- How do you respond to downturns? does your company continue to build for the long term even during difficult times?

- “We see good news and bad news in this chapter. The good news is that one of the key elements of being a visionary company is strikingly simple: Good old-fashioned hard work, dedication to improvement, and continually building for the future will take you a long way. It’s pretty straightforward stuff, easily within the grasp of every manager. The bad news is that creating a visionary company requires huge quantities of good old-fashioned hard work, dedication to improvement, and continually building for the future. There are no shortcuts. There are no magic potions. There are no work-arounds. To build a visionary company, you’ve got to be ready for the long, hard pull. Success is never final. It’s a lesson Howard Johnson never learned.”

- “Picture a martial artist kneeling before the master sensei in a ceremony to receive a hard-earned black belt. After years of relentless training, the student has finally reached a pinnacle of achievement in the discipline. “Before granting the belt, you must pass one more test,” says the sensei. “I am ready,” responds the student, expecting perhaps one final round of sparring. “You must answer the essential question: What is the true meaning of the black belt?” “The end of my journey,” says the student. “A well-deserved reward for all my hard work.” The sensei waits for more. Clearly, he is not satisfied. Finally, the sensei speaks. “You are not yet ready for the black belt. Return in one year.” A year later, the student kneels again in front of the sensei. “What is the true meaning of the black belt?” asks the sensei. “A symbol of distinction and the highest achievement in our art,” says the student. The sensei says nothing for many minutes, waiting. Clearly, he is not satisfied. Finally, he speaks. “You are still not ready for the black belt. Return in one year.” A year later, the student kneels once again in front of the sensei. And again the sensei asks: “What is the true meaning of the black belt?” “The black belt represents the beginning—the start of a never-ending journey of discipline, work, and the pursuit of an ever-higher standard,” says the student. “Yes. You are now ready to receive the black belt and begin your work””

- “We’ve done our best to discover and teach here the fundamental underpinnings of truly outstanding companies that have stood the test of time. We’ve given you an immense amount of detail and evidence in this book, and we expect that few readers will remember every little item in these pages. But as you walk away from reading this book, we hope you will take away four key concepts to guide your thinking for the rest of your managerial career, and to pass on to others. These concepts are: 1. Be a clock builder—an architect—not a time teller. 2. Embrace the “Genius of the AND.” 3. Preserve the core/stimulate progress. 4. Seek consistent alignment. We feel a bit like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz, who after her long journey in search of the wizard, pulls back the curtain and discovers that the wizard isn’t a wizard after all. He’s just a normal human being. Like Dorothy, we discovered that those who build visionary companies are not necessarily more brilliant, more charismatic, more creative, more complex thinkers, more adept at coming up with great ideas—in short, more wizardlike—than the rest of us. What they’ve done is within the conceptual grasp of every manager, CEO, and entrepreneur in the world. The builders of visionary companies tend to be simple—some might even say simplistic—in their approaches to business. Yet simple does not mean easy. We think this has profound implications for what you take away from this book. It means that no matter who you are, you can be a major contributor in building a visionary company. You don’t have to wait for the great charismatic visionary to descend from the mount. You don’t have to hope for the lightning bolt of creative inspiration to strike with the “great idea.” You don’t have to accept the debilitating perspective of “Well, let’s face it. Our CEO just isn’t a charismatic visionary leader. It’s hopeless.” You don’t have to buy into the belief that building visionary companies is something mysterious that only other people do. It also means that life will probably be more difficult for you from here on. It means helping those around you to understand the lessons of this book. It means accepting the frightening truth that you are probably as qualified as anyone else to help your organization become visionary. And it means recognizing that you can begin right now—today—to apply the lessons of this book. Finally, and perhaps most important of all, it means working with a deep and abiding respect for the corporation as an important social institution in its own right—an institution that requires the care and attention we give to our great universities or systems of government. For it is through the power of human organization—of individuals working together in common cause—that the bulk of the world’s best work gets done. So this is not the end. Nor even the beginning of the end. But it is, we hope, the end of the beginning—the beginning of the challenging and arduous, but eminently doable task of building a visionary company.”

- A well-conceived vision brings two elements together: core ideology and envisioned future. It unites the seemingly-paradoxical combination of preserving the core while stimulating process. It defines “what we stand for and why we exist” that does not change – the core ideology, and sets for what we aspire to become, to achieve and to create that will require significant change and progress to attain.

- Core ideology: is what defines you – enduring character, regardless of leaders, technological innovation, process improvement, new ways of doing business. it transcends all of that. It is knowing who you are. It is the one thing that will bring the organization together even as it decentralizes, grows and morphs over time. Core ideology is made up of two components: core values and core purpose

- Core Values: These are principles we believe to be true at all times regardless of the external environment around us, to the point where they can sometimes be a competitive disadvantage and we’d still hold on to these principles. They define who you are, what your belief system is and have an intrinsic value to you. They withstand the test of time. They will not change even if you were to go create a different company in a different industry. They require no external justification. They dictate the strategy – which is how you go about carrying out these principles in your life. They should be no more than 6 – not to be confused with strategy. The ultimate question to test whether a principle is a value is to see if you’d keep it in time of adversity – when external circumstances make holding on to the principle difficult.

- Core purpose: why you exist beyond making money.

“An effective purpose reflects the importance people attach to the company’s work—it taps their idealistic motivations—rather than just describing the organization’s output or target customers. It captures the soul of the organization. Purpose gets at the deeper reasons for an organization’s existence beyond just making money, as illustrated by a 1960 speech by David Packard, wherein he said: “I think many people assume, wrongly, that a company exists simply to make money. While this is an important result of a company’s existence, we have to go deeper and find the real reasons for our being.”” - “One powerful method for getting at purpose is the “Five Whys.” Start with the descriptive statement, “We make X products” or “we deliver X services,” and then ask “why is that important?” five times. After a few whys, you’ll find that you’re getting down to the fundamental purpose of the organization.”

- “Another approach is to ask each member of the Mars Group to answer the following questions: If you woke up tomorrow morning with enough money in the bank that you would never need to work again, how could we frame the purpose of this organization such that you would want to continue working anyway? What deeper sense of purpose would motivate you to continue to dedicate your precious creative energies to this company’s efforts? As we move into the 21st century, companies will need to draw on the full creative energy and talent of their people. But why should people give this level of commitment and devotion? As Peter Drucker has pointed out, the best and most dedicated people are ultimately volunteers, for they have the opportunity to do something else with their lives. With an increasingly mobile society, cynicism about corporate life, and an expanding entrepreneurial segment of the economy, companies need more than ever to have a clear understanding of their purpose in order to make work meaningful and thereby attract, retain, and motivate outstanding people.”

- “You do not “create” or “set” core ideology. You discover core ideology. It is not derived by looking to the external environment; you get at it by looking inside. It has to be authentic. You can’t fake an ideology. Nor can you just “intellectualize” it. Do not ask, “What core values should we hold?” Ask instead: “What core values do we actually hold?” Core values and purpose must be passionately-held on a gut level or they are not core. Values you think the organization “ought” to have, but that you cannot honestly say that it does have, should not be mixed into the authentic core values. To do so creates cynicism throughout the organization (Who are they trying to kid? We all know that isn’t a core value around here!”). Such aspirations of what you’d like to become are more appropriate as part of your envisioned future or as part of your strategy, not part of the core ideology. The role of core ideology is to guide and inspire, not to differentiate; it’s entirely possible that two companies can have the same core values or purpose. Many companies could have the purpose “to make technical contributions,” but few live it as passionately as HP. Many companies could have the purpose “to preserve and improve human life,” but few hold it as deeply as Merck. Many companies could have the core value of “heroic customer service,” but few create an intense cult-like culture around that value like Nordstrom does. Again, it’s not the content of the ideology that makes a company visionary, it’s the authenticity, discipline, and consistency with which the ideology is lived—the degree of alignment—that differentiates visionary companies from the rest of the pack. It’s not what you believe that sets you apart so much as that you believe in something, that you believe in it deeply, that you preserve it over time, and that you bring it to life with consistent alignment. Core ideology need only be meaningful and inspirational to people inside the organization; it need not be exciting to all outsiders. It’s the people inside the organization that need to be compelled by the core values and purpose to generate long-term commitment to the organization’s success. The effect your core ideology has on people outside the organization is less important and should not be the determining factor in identifying the core ideology. Core ideology therefore plays an essential role in determining who’s inside and who’s outside the organization. A clear and well-articulated ideology attracts people to the company whose personal values are compatible with the company’s core values and, conversely, repels those whose personal values are contradictory. You cannot “install” new core values or purpose into people. Core values and purpose are not something people “buy in” to. People must already have a predisposition to holding them. Executives often ask, “How do we get people to share our core ideology?” You don’t. You can’t! Instead, the task is to find people who already have a predisposition to share your core values and purpose, attract and retain these people, and let those who aren’t disposed to share your core values go elsewhere. Indeed, the very process of articulating core ideology may result in some individuals choosing to leave when it becomes clear that they are not personally compatible with the organization’s core—a positive cathartic outcome, not one to be avoided. Of course, you can (indeed should) still have diversity within the tight core ideology; just because people share the same core values or purpose does not mean that they all think or look the same.

- “Don’t confuse core ideology with “statements” of the core ideology. A company can have a very strong core ideology without a formal statement. For example, Nike has not (to our knowledge) formally articulated a statement of its core purpose. Yet, from our observations, Nike has a powerful core purpose that permeates the entire organization with a cult-like fervor: To experience the emotion of competition, winning, and crushing competitors. Nike has a campus that seems more like a shrine to the competitive spirit than a corporate office complex; giant photos of Nike heroes cover the walls, bronze plaques of Nike athletes hang along the Nike “Walk of Fame,” statues of Nike athletes stand along side the running track that rings the campus, and buildings are named after champions like Olympic marathon champion Joan Benoit, basketball superstar Michael Jordan, and tennis player John McEnroe.”

- “Envisioned future—the second primary component of the vision framework—consists of two parts: a ten- to thirty-year “Big Hairy Audacious Goal” and vivid descriptions of what it will be like when the organization achieves the BHAG. We selected the phrase “envisioned future,” recognizing that it contains a paradox. On the one hand, it conveys a sense of concreteness—something vivid and real; you can see it, touch it, feel it. On the other hand, it portrays a time yet unrealized—a dream, hope, or aspiration.”

- Creating a visionary BHAG requires 10-30 years to complete which necessitates thinking about the future beyond the current trends and environment. It should force you to think about the vision not the strategy or tactics. You should have about a 50%-70% of success. Should require extraordinary amount of work and a little of luck to accomplish.

A BHAG could be based on quantitative or qualitative achievements:

Become a $125bn company by the year 2000 (Wal-Mart)

Democratizing automobile (Ford)

They can focus on beating an external enemey:

Crush Adidas (Nike, 1960)

Or they can be an inspiration to emulate the success of another company – especially effective for small and upcoming ambitious comapnies

Become the Harvard of the West (Stanford, 1940) - “Vivid description, the second component of envisioned future, is a vibrant, engaging, and specific description of what it will be like to achieve the BHAG. Think of it as translating the vision from words into pictures, of creating an image that people can carry around in their heads. We call this “painting a picture with your words.” This “picture-painting” is essential for making the ten- to thirty-year BHAG tangible in people’s minds.

Passion, emotion, and conviction are essential parts of the vivid description. Some managers are uncomfortable with expressing emotion about their dreams, but it’s the passion and emotion that will attract and motivate others. Winston Churchill understood this when he described the BHAG facing Great Britain in 1940. He didn’t just say “Beat Hitler.” He said: Hitler knows he will have to break us on this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, the whole world including the United States, including all we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age, made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour.”” - Do not spend time creating a BHAG vision goal based on analysis – trying to analyze your way into the future. Start instead by answering questions such as ““We’re sitting here in twenty years; what would we love to see? What would this company look like? What would it feel like to employees? What would it have achieved?” The goal should serve the purpose of stimulating progress, generating excitement among people involved, and desire to put the hard work required for success. Don’t worry about analyzing whether an envisioned future is the “right” one. With a creation, there can be no right answer – the task is to create a future not predict the future.

- “Q: I’M NOT CEO. WHAT CAN I DO WITH THESE FINDINGS? Plenty. First, you can apply most of our findings in your work area, albeit on a smaller scale. You can be a clock builder at any level, for this is a state of mind as much as a method of operating. Instead of instinctively jumping in to solve a problem in the heroic leader mode, ask first, “What process should we use to solve this problem?” You can build a cult-like culture around a strong ideology at any level. Of course, it will be constrained somewhat by the ideology of the overall organization, but it can be done. And if the overall company doesn’t have a clear ideology, then all the more reason (and freedom) to put one in place at your level! Just because the corporation as a whole might not have a strong core ideology doesn’t mean your group should be deprived. One manufacturing manager for a computer company told us: “I got tired of waiting for those on top to get their act together, so I just went ahead with my people. We now have a very distinct set of values here in my group, and we manage by them. It gives my people a greater sense of meaning in their work. We have a strong self-identity within the company, and we interview people with an eye to how they’ll fit with our team. People feel they belong to something special. We even have our own jackets and caps.” You can also stimulate progress at any level. We’ve seen BHAGs work particularly well at midlevels. A real estate operations manager within a larger company asks every single employee and manager in her group to set a personal BHAG for each year. She also sets a BHAG for the entire group. And there’s no reason why you can’t create a group culture that encourages people to try a lot of stuff and keep what works. Why not put in place a 3M-style 15 percent rule in your group? Why not invent mechanisms of discontent to stimulate change and improvement before you’re forced to change and improve?

Another powerful step you can take is to educate those around you about the key findings from the companies we studied. Help them understand the importance of building the organization, rather than just building the next great product. Help them understand the concept of preserving the core and stimulating progress. Point out to people where the organization is misaligned and why alignment is so vital. Help them reject the Tyranny of the OR. For example, one middle manager we know frequently gets people unstuck during meetings by saying, “Hey, I think we’re succumbing to the ‘Tyranny of the OR’ here. Let’s find a way to embrace the ‘Genius of the AND.’ ” And they usually do. You can use the visionary companies as a source of immense credibility. For example, if senior executives resist articulating core values or purpose as too “soft” or “new age,” point to Hewlett-Packard, Merck, 3M, Procter & Gamble, Sony, and others in this book—and point to how they’ve done this for decades. How can any hard-nosed executive argue with the long-term track record of these companies? Indeed, you can use these companies as credibility to virtually demand that senior management pay attention. What executive could not be interested in attaining the enduring stature of these companies?”

- “Q: ARE THERE ANY PEOPLE WHO CAN’T BUILD A VISIONARY COMPANY? Few. The only people who can’t do it are those unwilling to persist for the long haul, those who like to rest on their laurels, those with no core ideology, and those who do not care about the health of the company after they’re gone. If you want to start a company, build it quickly, make a lot of money, cash out, and retire, then building a visionary company is not for you. If you don’t have a drive for progress—an internal urge to never stop improving and going forward for its own sake—then building a visionary company is not for you. If you don’t have any interest in a values-driven company with a sense of purpose beyond just making as much money as possible, then building a visionary company is not for you. If you don’t care about building the company so that it will be strong not only during your tenure but also decades after you’re gone, then building a visionary company is not for you. But beyond these four, we see no other prerequisites.”