- ” I don’t primarily think of my work as about the study of business, nor do I see this as fundamentally a business book. Rather….I’m curious to understand fundamental differences between great and good, between excellent and mediocre. I just happen to use corporations as a means of getting inside the black box. “

- “Good is the enemy of great, and that is one of the key reasons why we have so little that becomes great. We don’t have great schools, principally because we have good schools. We don’t have a great government, principally because we have good government. Few people attain great lives, in large part because it is just so easy to settle for a good life. The vast majority of companies never become great, precisely because the vast majority become quite good-and that is their main problem. ”

- One surprising conclusion that the author found was that almost any organization can substantially improve its stature and performance, perhaps become great, if it consistently applied the framework of ideas uncovered.

- “People often ask, “What motivates you to undertake these huge research projects?” It’s a good question. The answer is, “Curiosity.” There is nothing I find more exciting than picking a question that I don’t know the answer to and embarking on a quest for answers.”

- Some of the unexpected findings that the author uncovered during his quest include:

- Mergers and acquisitions played no role in turning a company from good to great

- Hiring a celebrity CEO from outside of the company didn’t help either. Change almost came with a CEO from within

- Element of planned change management was largely not needed as companies under the right conditions found that the problems of commitment, alignment, motivation and change largely melt away

- Strategy per se did not separate good-to-great companies from comparison companies. No evidence found of companies spending more time on long-range strategic planning than the comparison companies

- Industry or technologies did not play a principle role in the transformation from good to great.

- First who, then what: we expected great leaders to begin by setting a new vision and strategy. Instead, they focused on people first. They made sure that they got the wrong people off the bus, the right people on the bus, and the right people in the right seats. “The right people are your most important asset”

- Good to great companies embodied the principle of never losing faith that you can and will prevail at the end, yet you have the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they may be.

- Level5 leaders embody the paradox of humility and fearless will to achieve goals.

- Level5 leaders display a workmanlike diligence – a plow horse rather than a show horse

- Good-to-great leaders began with who- people, rather than what – strategy or vision, for three reasons:

- If you began with the what and then you realized shortly that you need to change it – due to unforeseen circumstances, you’d face a problem of having people who were with you for a specific vision but now you have a completely different vision. Instead, if you have the right people, they’d adapt to changing vision

- If you have the right people, you don’t have to spend time firing them up and motivating them. The right people were self-motivated by inner drive to produce the best results.

- If you had the wrong people, it won’t matter whether you discover the right direction, you still won’t have a great company

- ” Instead of mapping out a strategy for change, he and chairman Ernie Arbuckle focused on “injecting an endless stream of talent” directly into the veins of the company. They hired outstanding people whenever and wherever they found them, often without any specific job in mind. “That’s how you build the future,” he said. “If I’m not smart enough to see the changes that are coming, they will. And they’ll be flexible enough to deal with them.””

- “Wells Fargo’s approach was simple: You get the best people, you build them into the best managers in the industry, and you accept the fact that some of them will be recruited to become CEOs of other companies.’ Bank of America took a very different approach. While Dick Cooley systematically recruited the best people he could get his hands on, Bank of America, according to the book Breaking the Bank, followed something called the “weak generals, strong lieutenants7 ‘ model.8 If you pick strong generals for key positions, their competitors will leave. But if you pick weak generals-placeholders, rather than highly capable executivesthen the strong lieutenants are more likely to stick around. The weak generals model produced a climate very different at Bank of America than the one at Wells Fargo. Whereas the Wells Fargo crew acted as a strong team of equal partners, ferociously debating eyeball-to-eyeball in search of the best answers, the Bank of America weak generals would wait for directions from above. Sam Armacost, who inherited the weak generals model, described the management climate: “I came away quite distressed from my first couple of management meetings. Not only couldn’t I get conflict, I couldn’t even get comment. They were all waiting to see which way the wind blew.”

- In contrast of the good-to-great companies who focused on bringing exceptional talent, other companies focused on a “one genius model with thousands of helpers”

- “Nucor illustrates a key point. In determining “the right people,” the good-to-great companies placed greater weight on character attributes than on specific educational background, practical skills, specialized knowledge, or work experience. Not that specific knowledge or skills are unimportant, but they viewed these traits as more teachable (or at least learnable), whereas they believed dimensions like character, work ethic, basic intelligence, dedication to fulfilling commitments, and values are more ingrained. As Dave Nassef of Pitney Bowes put it: I used to be in the Marines, and the Marines get a lot of credit for building people’s values. But that’s not the way it really works. The Marine Corps recruits people who share the corps’ values, then provides them with the training required to accomplish the organization’s mission. We look at it the same way at Pitney Bowes. We have more people who want to do the right thing than most companies. We don’t just look at experience. We want to know: Who are they? Why are they? We find out who they are by asking them why they made decisions in their life. The answers to these questions give us insight into their core values”

- “To be rigorous in people decisions means first becoming rigorous about top management people decisions. Indeed, I fear that people might use “first who rigor” as an excuse for mindlessly chopping out people to improve performance. “It’s hard to do, but we’ve got to be rigorous,” I can hear them say. And I cringe. For not only will a lot of hardworking, good people get hurt in the process, but the evidence suggests that such tactics are contrary to producing sustained great results. The good-to-great companies rarely used head-count lopping as a tactic and almost never used it as a primary strategy”

- How to be Rigorous:

- Practical Discipline #1: When in doubt, don’t hire-keep looking.

- Practical Discipline #2: When you know you need to make a people change, act. The moment you feel the need to tightly manage someone, you’ve made a hiring mistake. The best people don’t need to be managed. Guided, taught, led-yes. But not tightly managed. We’ve all experienced or observed the following scenario. We have a wrong person on the bus and we know it. Yet we wait, we delay, we try alternatives, we give a third and fourth chance, we hope that the situation will improve, we invest time in trying to properly manage the person, we build little systems to compensate for his shortcomings, and so forth. But the situation doesn’t improve

- Good-to-Great companies did not churn employees more than other companies. Instead they churned better. There was a pattern: employees stuck with them for either a long-time or left rather quickly. Having said that, it is important to take your time to make sure that an employee is not an A+ employee and that their performance is not just a function of them being at the wrong place. Two criteria that helps with that:

- If it were a hiring decision, rather than a firing decision, would you hire the person again?

- Second, if the person came to tell you he or she is pursuing an exciting new opportunity, would you feel terribly disappointed or secretly relieved?

- Principle 3: put your best people to the greatest opportunities, not problems. Dedicating them to dealing with problems will only make you good, not great.

Members of the good-to-great teams tended to become and remain friends for life. In many cases, they are still in close contact with each other years or decades after working together. It was striking to hear them talk about the transition era, for no matter how dark the days or how big the tasks, these people had fun! They enjoyed each other’s company and actually looked forward to meetings. A number of the executives characterized their years on the good-to-great teams as the high point of their lives. Their experiences went beyond just mutual respect (which they certainly had), to lasting comradeship.

Adherence to the idea of “first who” might be the closest link between a great company and a great life. For no matter what we achieve, if we don’t spend the vast majority of our time with people we love and respect, we cannot possibly have a great life. But if we spend the vast majority of our time with people we love and respect-people we really enjoy being on the bus with and who will never disappoint us-then we will almost certainly have a great life, no matter where the bus goes. The people we interviewed from the good-to-great companies clearly loved what they did, largely because they loved who they did it with - The moment a leader allows themselves to become the primary reality people worry about, rather than reality being the primary reality, you have a recipe for mediocrity. This is one of the key reasons why charismatic leaders often produce long-term results rather than more charismatic counterparts.

- 5 things to do to ensure that truth is heard:

- Lead with questions

- Encourage dissent

- Red flag mechanism: allow people to voice their opinions in a way that is not open to misinterpretation.

- Lead by example

- Conduct autopsies without blame.

- “This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end-which you can never afford to lose-with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.” To this day, I carry a mental image of Stockdale admonishing the optimists: “We’re not getting out by Christmas; deal with it!”

- The Stockdale Paradox: “Retain faith that you will prevail and achieve your goals, regardless of the difficulties AND Confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

- You could be a fox or a hedgehog. Foxes know many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

However, hedgehogs do one thing exceptionally well: they know how to protect themselves. Each day the fox devises new strategies to attack the hedgehog, waiting for that perfect moment to strike and surprise the hedgehog. Yet, the hedgehog turns into a ball of sharp spines that protects it from the fox attack. And the scene repeats itself. - “Berlin extrapolated from this little parable to divide people into two basic groups: foxes and hedgehogs. Foxes pursue many ends,at the same — time and see the complexity. They are “scattered or diffused, moving on many levels,” says Berlin, never integrating their thinking into one overall concept or unifying vision. Hedgehogs, on the other hand, simplify a complex world into a basic principle-or one overall concept that unifies and guides everything. ” It doesn’t matter how complex the world, a hedgehog reduces all challenges and dilemmas to simple indeed almost simplistic-hedgehog ideas. For a hedgehog, anything that does not somehow relate to the hedgehog idea holds no relevance. Princeton professor Marvin Bressler pointed out the power of the hedgehog during one of our long conversations: “You want to know what separates those who make the biggest impact from all the others who are just as smart? They’re hedgehogs.” Freud and the unconscious, Darwin and natural selection, Marx and class struggle, Einstein and relativity, Adam Smith and division of labor-they were all hedgehogs. They took a complex world and simplified it. “Those who leave the biggest footprints,” said Bressler, “have thousands calling after them, ‘Good idea, but you went too far!’ “

- Those who led good to great companies were hedgehogs They used their drive toward what we came to call a Hedgehog concept for their companies.

- A Hedgehog Concept is a simple, crystalline concept that flows from deep understanding of the intersection of the following three circles:

- What you can be the best in the world at: this goes beyond core competency

- What drives your economic engine: How to most effectively generate sustained cash flow.

- What you are deeply passionate about.

- I do think though that a hedgehog concept could be the intersection of knowing one’s core capability, where they want to be and the circumstances in which they can put this core capability to work to achieve the end goal

- The hedgehog concept is not a goal to be the best, a strategy to be the best, an intention or plan to be the best. Rather it is built on an understanding of what you can be the best at. Crucial distinction.

- Walgreens: The metric Profit/Customer Visit is their key driver for their financial engine. The industry standard metric of profit/store actually was contradictory to their purpose – convenience. If they based decisions on store location on profit/store, they would not be able to justify putting the stores so close together; the economics would not make sense. But, since they were committed to convenience, they discovered that their financial engine actually ran on profit/customer visit. Therefore, they make strategic choices that increase the likelihood that people coming into Walgreens because it is conveniently located will spend more money each time they visit.

- Nucor: understood that it made its profit per ton of finished steel. having a denominator of per employee or per fixed cost would have been simpler but it wouldn’t reflect Nucor understanding that the driving force in its economic engine was a combination of strong-work-ethic culture and the application of advanced manufacturing technology.

- The three circles that should guide what you pursue as an individual or an organization: what is it that your passionate about? what is it that you can be the best in the world at – not just very successful? Do you really understand the drivers in your economic engine, including your economic denominator?

Companies could form a Council – a group of people who debate questions created based off the three circles, debate the answers, make decisions guided by the three circles, and auotposy the analysis.

- To accelerate the process of getting the Hedgehog Concept, you need to increase the number of times you go around the full cycle in a given period of time. If you go through this cycle enough time, you will give an indepth understanding required for the Hedgehog concept. It will not happen overnight, but it will happen eventually.

- Not all good-to-great companies had a Hedgehog concept or were the best in the world at what they did, but every good-to-great company prevailed at the end in its search for it Hedgehog Concept no matter how awful the start of the process.

- Jim Collins brings up a family example to illustrate the Hedgehog concept: his wife Joanne had participated in triathlon competitions. One time, she competed with women who have won triathlon championships before. She was in the top 10 despite a very poor showing in the swimming part and despite having to carry a heavy bike uphill.

Three weeks later while she was sitting with Jim, she stated ” I could win ironman”. It was stated as a simple fact to her. She quit her job, and after three years, she beame the world ironman championship in 1985. - “Freedom is only part of the story and half the truth. That is why I recommend that the Statute of LIberty on the East Coast by supplanted by a Statute of Responsibility on the West Coast”

- “Why start this chapter with a biotechnology entrepreneur rather than one of our good-to-great companies? Because Rathmann credits much of his entrepreneurial success to what he learned while working at Abbott Laboratories before founding Amgen: What I got from Abbott was the idea that when you set your objectives for the year, you record them in concrete. You can change your plans through the year, but you never change what you measure yourself against. You are rigorous at the end of the year, adhering exactly to what you said was going to happen. You don’t get a chance to editorialize. You don’t get a chance to adjust and finagle, and decide that you really didn’t intend to do that anyway, and readjust your objectives to make yourself look better. You never just focus on what you’ve accomplished for the year; you focus on what you’ve accomplished relative to exactly what you said you were going to accomplish-no matter how tough the measure. That was a discipline learned at Abbott, and that we carried into Amgen.“

- Much of Abbott disciplines go back to 1968, when it hired a remarkable financial officer named Bernard H. Semler. Semler did not see his job as a traditional financial controller or accountant. Rather, he set out to invent mechanisms that would drive cultural change. He created a whole new framework of accounting that he called Responsible Accounting. Wherein every item of cost, income, investment would be clearly associated with a single individual responsible for that item. The idea – radical for the 1960s, was to create a system where every Abbott manager in every type of job was responsible for his or her return on investment with the same rigor an investor held an entrepreneur accountable.

Abbott Hedgehog concept was that it maintained an environment where creativity and innovation were encouraged, yet maintaining financial adherence to the principle of cost-effective healthcare. - Abbott exemplified the culture of discipline. By its nature, culture is somewhat of an wieldy topic to discuss, less prone to clean frameworks like the three circles. The main point to emphasize is to build a culture full of people who take disciplined action within the three circles, financially consistent with the Hedgehog Concept.

- Build a culture around the idea of freedom and responsibility, within a framework

- find people who are self-disciplined and willing to go to extreme lengths to fulfill their responsibilities. They will “rinse their cottage cheese”

- Don’t confuse discipline with tyranny.

- Adhere with great consistency to the Hedgehog Concept, exercising an almost religious focus on the intersection of the three circles.

- Much of this book is dedicated to explaining the Culture of Discipline. It begins with hiring disciplined people whom you can take the business on a journey to success. you cannot discipline wrong people into the right behaviors. Next you have disciplined the though. After, you will need the discipline to face brutal facts, while maintaining resolute belief that you can and will create a path to greatness. Most importantly, you need the discipline to develop an understanding of the hedgehog concept. Finaly, there is disciplined actions. Comparison companies jump into disciplined action immediately.

- Discipline by itself will not produce great results. Companies have driven themselves to failure – with precision and in nicely formed lines. The point is to first get those self-disciplined people who engage in very rigorous thinking, who take the freedom within the disciplined framework of a consistent designed within the confounds of the Hedgehog Concept.

- People in the good-to-great companies took the concept of discipline to a new extreme, bordering in some cases on fanaticism.

- This is called “rinsing your cheese factor” and it comes from a 6-time Ironma World Championship winner. He would run 17miles, swims 20k, and ride his bike for 75miles a day. He firmly believed that having a diet rich in carbohydrates and low in fat would help him in achieving his goal. As a result, he rinsed off the cheese before eating it just to get rid of excess fat. While there is no scientific proof that what he did was needed, the idea is to show the extreme lengths he went to stick to his discipline.

- In a culture of discipline, you don’t just jump into action. instead, you have disciplined people who have disciplined thoughts that translate into disciplined actions.

- The single most important thing that good to great companies do is that they adhere religiously to the hedgehog concept: finding ideas that fit within the intersection of three circles: passion, best in the world, and the thing that has the greatest impact on revenue. they are willing to let all other ideas pass them by while resisting the temptation to swing.

- there is a massive difference between tyranny and disciplined cultures. Companies that depend solely on a single person to turn things around, who uses their charisma and authority to force change will not be successful.

- bureaucratic cultures arise to compensate for incompetence and lack of discipline, which arise from having the wrong people on the wrong bus in the first place. if you get the right people on the bus and the wrong people off the bus, you don’t need styfiling bureaucracy.

- the fact that something is “once in a lifetime opportunity” is irrelevant, unless it fits within the three circles. A great company will have many once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

- In the late 1999 and early 2000s, there was a huge frenzy surrounding the potential that the internet has on ways of doing business. Analysts and the public became more fixated on the potential that anything that launched on the internet had as opposed to focusing on sales, revenues, earnings, and the soundness of the business idea.

one company went public based simply on having an information website and just a business plan. there was company, no employees, no revenue, and yet people bought shares of that company at 7 and 9 dollars.

drugstore.com debuted into the stock market in July of 1999. The price of the stock went parabolic. Analysts doubted Wallgreens ability to respond quickly to the changing business landscape, declaring that technology wins. you need to move first, move fast, and have an internet presence as the recipe for success - Wallgreens’ CEO at the time declared that his company will be methodical in responding to this changing landscape. His company crawls, walks, runs. Internally the company had full conviction that it will succeed but also recognized the brutal reality of changing business landscape. They started crawling by having customers place their prescription online and have them quickly collect it at the stores until they have launched the fully-fledged e-commerce website in summer of 2000. The price of the stock doubled while drugstore.com was crashing.

- Technology without a hedgehog concept and strict adherence to the three-circles concept cannot make a company great. Technology can accelerate a company momentum but cannot create momentum on its own.

- When you think of technology as being the single key to success, think again of Vitenam.

Technology can be a liability not an asset if it is relied upon thoughtlessly. - Those who built good-to-great companies were not motivated by fear of missing out – watching others hit when they did not. They weren’t driven by fear of what they didn’t understand or looking like a chump. They weren’t driven by fear of being hammered out by the competition. instead they were driven by a relentless thirst for the highest degree of excellence attainable.

- Technology can be an accelerator of change not the cause of it. The key question to ask about technology is: does it fit directly with your Hedgehog Concept? if yes, you need to become a pioneer in the application of that technology.

- If you were to take all the technology tools that good-to-great companies have and gave it to mediocre companies, it wouldn’t change their mediocrity.

- How a company reacts to technology is a good indicator of its internal drive to success: fear of failure of excellence.

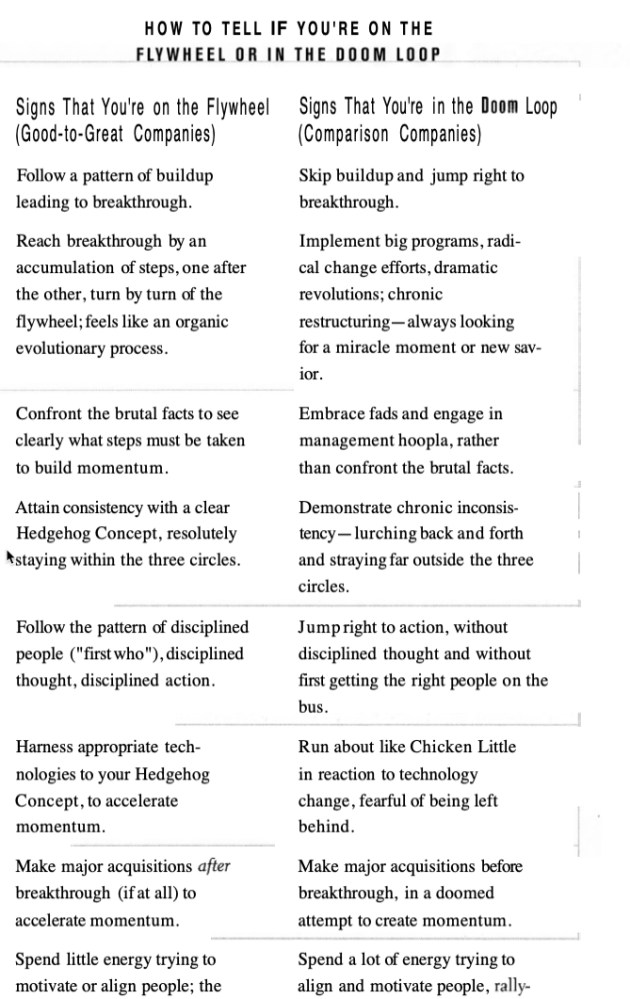

- Good-to-great companies did not achieve their great success as a result of a single event, rather it was a cumulative process – step by step, action by action, decision by decision, turn by turn of the flywheel that adds up to sustained and spectacular results.

A good analogy of it is to think of a big flywheel, placed horizontally on an axle. To rotate as fast and as long as possible, you will have to go rotating it the first time which is hard, then the momentum builds in it as you rotate it one time after another. - We have allowed the way successful transitions look like from the outside to drive our perception of what they must feel like to those going through them on the inside. From the inside though, it was an organic developmental process.

It is similar to the development of an egg to a chicken. For an outsider, it seems as if the change happened overnight: the egg turned into a chicken. But the chicken had to develop, incubate, grow and evolve until it reached that moment. - Jim Herring, the Level5 leader at Kroeger, explains how he transformed the company. He refrained from motivation and hoopla. Instead, he focused on turning the flywheel, round after round, until it started gathering momentum. he shared with the team the tangible outcome of the work and linked it clearly to it. This way people would gain confidence from the successes not just the words.

- Leaders could mistakenly use acquisitions as a way to create success not accelerate its momentum. Before doing any acquisitions that make the CEO look good or diversifying away the troubles, these companies need to realize what it is that they are the best at in the world, fits the economic denominator and have a great passion for.

- Summary of the entire recipe of good-to-great:

it starts with a Level5 Leader, one who is not interested in getting recognition for leading or for making big and radical moves that do not align with the passion, what the company can be the best at or what the most important denominator is for revenue. They realize that motivation and hoopla is not the way to get the team to work consistently to achieve excellence.

Instead, they begin by cleaning up the house – who should be on the bus vs who should be off the bus. They create a flywheel virtuous cycle by demonstrating how following the action plan consistently leads to tangible success – even if they start with small successes.

Equally important to them is to remember the Stockdale Paradox “we’re not going to hit breakthrough by Christmas, but if we keep pushing in the right direction, we will eventually hit breakthrough.” This process of confronting the brutal facts helps you see the obvious, albeit difficult, steps that much be taken to turn the flywheel. Faith in the endgame helps you live through the months or years of buildup.

Next, you attain very deep understanding about the three circles of your hedgehog concept and begin to push in a direction consistent of that understanding. You hit breakthrough momentum and accelerate with key accelerators, such as technology and acquisitions. The key is that these accelerators are tied back directly to the three circles. Ultimately, to reach breakthrough means having the discipline to make a series of good decisions consistent with your Hedgehog Concept – disciplined action, following from disciplined people who exercise disciplined though. That’s it. That is the essence of the breakthrough process. -

“Consider, for example, the buildup-breakthrough flywheel pattern in the evolution of Wal-Mart. Most people think that Sam Walton just exploded onto the scene with his visionary idea for rural discount retailing, hitting breakthrough almost as a start-up company. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Sam Walton began in 1945 with a single dime store. He didn’t open his second store until seven years later. Walton built incrementally, step by step, turn by turn of the flywheel, until the Hedgehog Concept of large discount marts popped out as a natural evolutionary step in the mid- 1960s. It took Walton a quarter of a century to grow from that single dime store to a chain of 38 Wal-Marts. Then, from 1970 to 2000, Wal-Mart hit breakthrough momentum and exploded to over 3,000 stores with over $150 billion (yes, billion) in revenues2 Just like the story of the chicken jumping out of the egg that we discussed in the flywheel chapter, Wal- Mart had been incubating for decades before the egg cracked open. As Sam Walton himself wrote:

Somehow over the years people have gotten the impression that Wal- Mart was. . . just this great idea that turned into an overnight success. But. . . it was an outgrowth of everything we’d been doing since [1945].. . . And like most overnight successes, it was about twenty years in the making.

If there ever was a classic case of buildup leading to a Hedgehog Concept, followed by breakthrough momentum in the flywheel, Wal-Mart is it. The only difference is that Sam Walton followed the model as an entrepreneur building a great company from the ground up, rather than as a CEO transforming an established company from good to great. But it’s the same basic idea.”

- Hewlett Packard: Bill Hewlett and David Packarad founded HP based on the idea that they wanted to bring like-minded smart people to work together. They did not have a product in mind yet. They spent months at first trying to figure out what product to focus on. They wanted to be in the electrical engineering field – the one they graduated from in school.

They experimented with a few ideas – A/C remote controls, yacht engines. The experiment would continue. Even after the second world war, HP continued with its principle of hiring the right talent even when they did not have specific jobs for them.

Hewlett maintained humility as HP grew to become one of the biggest tech companies at the time. As he became one of the first billionaires of Silicon Valley, he still attributed the company’s success to luck. He still lived in the same old home he built together with his wife in 1957. His favorite spare time was to string some barbed wires. - “Hewlett-Packard provides another excellent example of the good-to- great ideas at work in the formative stages of a Built to Last company. For instance, Bill Hewlett and David Packard’s entire founding concept for HP was not what, but who- starting with each other. They’d been best friends in graduate school and simply wanted to build a great company together that would attract other people with similar values and standards. The founding minutes of their first meeting on August 23, 1937, begin by stating that they would design, manufacture, and sell products in the electrical engineering fields, very broadly defined. But then those same founding minutes go on to say, “The question of what to manufacture was postponed. . . .”

Hewlett and Packard stumbled around for months trying to come up with something, anything, that would get the company out of the garage. They considered yacht transmitters, air-conditioning control devices, medical devices, phonograph amplifiers, you name it. They built electronic bowling alley sensors, a clock-drive for a telescope, and an electronic shock jiggle machine to help overweight people lose weight. It didn’t really matter what the company made in the very early days, as long as it made a technical contribution and would enable Hewlett and Packard to build a company together and with other like-minded people.It was the ultimate

“first who . . . then what” start-up. Later, as Hewlett and Packard scaled up, they stayed true to the guiding principle of “first who.” After World War II, even as revenues shrank with the end of their wartime contracts, they hired a whole batch of fabulous people streaming out of government labs, with nothing specific in mind for them to do. Recall Packard’s Law, which we cited in chapter: “No company can grow revenues consistently faster than its ability to get enough of the right people to implement that growth and still become a great company.” Hewlett and Packard lived and breathed this concept and obtained a surplus of great people whenever the opportunity presented itself.

Hewlett and Packard were themselves consummate Level 5 leaders, first as entrepreneurs and later as company builders. Years after HP had established itself as one of the most important technology companies in the world, Hewlett maintained a remarkable personal humility. In 1972, HP vice president Barney Oliver wrote in a recommendation letter to the IEEE Awards Board for the Founders Award:

While our success has been gratifying, it has not spoiled our founders. Only recently, at an executive council meeting, Hewlett remarked: “Look, we’ve grown because the industry grew. We were lucky enough to be sitting on the nose when the rocket took off. We don’t deserve a damn bit of credit.” After a moment’s silence, while everyone digested this humbling comment, Packard said: “Well, Bill, at least we didn’t louse it up completely.”

Shortly before his death, I had the opportunity to meet Dave Packard. Despite being one of Silicon Valley’s first self-made billionaires, he lived in the same small house that he and his wife built for themselves in 1957, overlooking a simple orchard. The tiny kitchen, with its dated linoleum, and the simply furnished living room bespoke a man who needed no material symbols to proclaim “I’m a billionaire. I’m important. I’m successful.” “His idea of a good time,” said Bill Terry, who worked with Packard for thirty-six years, “was to get some of his friends together to string some barbed wire.’Is Packard bequeathed his $5.6 billion estate to a charitable foundation and, upon his death, his family created a eulogy pamphlet, with a photo of him sitting on a tractor in farming clothes. The caption made no reference to his stature as one of the great industrialists of the twentieth century.9 It simply read: “David Packard, 1912- 1996, Rancher, etc.” Level 5, indeed.”

-

“Hewlett and Packard exemplify a key “extra dimension ‘ that helped elevate their company to the elite status of an enduring great company, a vital dimension for making the transition from good to great to built to last. That extra dimension is a guiding philosophy or a “core ideology,” which consists of core values and a core purpose (reason for being beyond just making money). These resemble the principles in the Declaration of Independence (“We hold these truths to be self-evident ‘)- never perfectly followed, but always present as an inspiring standard and an answer to the question of why it is important that we exist.”

- Profit and cashflow are never the reason why great companies exist. Like blood and water, they are essential to life, but are not the point of life.

- Another important caveat is that it doesn’t matter what the core ideology is for a company as long as the company maintained it. A company need not have passion for customers (Sony), or respect for individual (Disney did not), or quality (Walmart did not), or social responsibility (Ford didn’t) in order to become enduring and great. The point is not what core values you have, but rather that you have core values, that you build them explicitly into the organization and that you preserve them over time.

How do you balance the tension of preserving these core principles yet adapt to a changing world? Embrace the concept of preserve the core/stimulate progress. - Walt Disney: founded on the idea of making cartoon movies. the core principles are: do not tolerate cynicism, bring happiness to children, fanatic attention to details and embracing creativity. Those principles were not compromised as Disney embraced and stimulated change- they got into theme parks, animation, and cruise lines.

- The principles that make good-to-great companies make a great foundation for the built-to-last companies that are great and want to remain great.

- Have a core ideology (which explains why a company exists beyond making money) that will be preserved religiously.

- Build a company whose success is not dependent on having one single person as a leader. Build an organization that can endure and adapt through multiple generations of leaders and multiple product life cycles.

- Stimulate change while preserving core values

- Embrace both extremes of a number of dimensions at the same time. Purpose AND profitability, continuity AND change, freedom AND responsibility

- The most suitable Big Hairy Audacious Goals to pursue are ones that fit within the three-circle intersection of the three circles of the Hedgehog concept. A bad BHAG is based on bravado, while a good BHAG is based on the understanding that brings together the audacity of a BHAG and the quiet understanding of the three circles.

An example that illustrates the above intersection is Boeing’s foray into commercial aircraft manufacturing in the 1950s. Boeing had to spend a quarter of its net worth to develop a prototype of the 707. Despite Boeing not having made a commercial aircraft before, they understood through deliberate thinking that they can be the best commercial aircraft manufacturer in the world, that they can increase their profitability per aircraft model and they were very passionate about the idea. - One might ask a question: Why strive for greatness? why not just be successful? what if I don’t want to build a great company?

The author offers a two-part answer to the question: greatness could be achieved in whichever field you’re in and regardless of the size of the venture you’re involved in. Boeing is an excellent example of striving for greatness but so is the building owner who sets the standards when it comes the quality of the units, the overall infrastructure of the building, and the usability of the office space. In other words, greatness does not require that the venture be of a specific size, industry, or type. As long as you strive to be the best in the world when it comes to what you do, that is greatness.

Second, if what you do is something you’re passionate about it, you can’t help but be great at it. This is why if you ask the question “what’s wrong with just being successful and not great?” you’re probably engaged in the wrong line of work/cause. - “Perhaps your quest to be part of building something great will not fall in your business life. But find it somewhere. If not in corporate life, then perhaps in making your church great. If not there, then perhaps a nonprofit, or a community organization, or a class you teach. Get involved in something that you care so much about that you want to make it the greatest it can possibly be, not because of what you will get, but just because it can be done.

When you do this, you will start to grow, inevitably, toward becoming a Level 5 leader. Early in the book, we wondered about how to become Level 5, and we suggested that you start by practicing the rest of the findings. But under what conditions will you have the drive and discipline to fully practice the other findings? Perhaps it is when you care deeply enough about the work in which you are engaged, and when your responsibilities line up with your own personal three circles.

When all these pieces come together, not only does your work move toward greatness, but so does your life. For, in the end, it is impossible to have a great life unless it is a meaningful life. And it is very difficult to have a meaningful life without meaningful work. Perhaps, then, you might gain that rare tranquillity that comes from knowing that you’ve had a hand in creating something of intrinsic excellence that makes a contribution. Indeed, you might even gain that deepest of all satisfactions: knowing that your short time here on this earth has been well spent, and that it mattered.”

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.