- “Entrenched myth: Successful leaders in a turbulent world are bold, risk-seeking visionaries. Contrary finding: The best leaders we studied did not have a visionary ability to predict the future. They observed what worked, figured out why it worked, and built upon proven foundations. They were not more risk taking, more bold, more visionary, and more creative than the comparisons. They were more disciplined, more empirical, and more paranoid.”

- “Entrenched myth: Innovation distinguishes 10X companies in a fast-moving, uncertain, and chaotic world. Contrary finding: To our surprise, no. Yes, the 10X cases innovated, a lot. But the evidence does not support the premise that 10X companies will necessarily be more innovative than their less successful comparisons; and in some surprise cases, the 10X cases were less innovative. Innovation by itself turns out not to be the trump card we expected; more important is the ability to scale innovation, to blend creativity with discipline. Entrenched myth: A threat-filled world favors the speedy; you’re either the quick or the dead. Contrary finding: The idea that leading in a “fast world” always requires “fast decisions” and “fast action”—and that we should embrace an overall ethos of “Fast! Fast! Fast!”—is a good way to get killed. 10X leaders figure out when to go fast, and when not to. Entrenched myth: Radical change on the outside requires radical change on the inside. Contrary finding: The 10X cases changed less in reaction to their changing world than the comparison.

Entrenched myth: Innovation distinguishes 10X companies in a fast-moving, uncertain, and chaotic world. Contrary finding: To our surprise, no. Yes, the 10X cases innovated, a lot. But the evidence does not support the premise that 10X companies will necessarily be more innovative than their less successful comparisons; and in some surprise cases, the 10X cases were less innovative. Innovation by itself turns out not to be the trump card we expected; more important is the ability to scale innovation, to blend creativity with discipline. Entrenched myth: A threat-filled world favors the speedy; you’re either the quick or the dead. Contrary finding: The idea that leading in a “fast world” always requires “fast decisions” and “fast action”—and that we should embrace an overall ethos of “Fast! Fast! Fast!”—is a good way to get killed. 10X leaders figure out when to go fast, and when not to. Entrenched myth: Radical change on the outside requires radical change on the inside. Contrary finding: The 10X cases changed less in reaction to their changing world than the comparison” - “So, we invite you to join us on a journey to learn what we learned. Challenge and question; let the evidence speak. Take what you find useful and apply it to creating a great enterprise that doesn’t just react to events but shapes events. As the influential management thinker Peter Drucker taught, the best—perhaps even the only—way to predict the future is to create it.”

- The author uses the story of the first two human teams that tried to reach to the pool as a way to illustrate the great results that great leadership achieves. The team led by Scott arrived 34 days late to the site in Antarctica and never made it back – they froze and died on the way back. The other team led by Amundsen made it back successfully. Both team started the quest within days from each other and had about the same distance to hike. Both were under extreme conditions – no cells or modern tech back in 1911.

- Amundsen bicycled for 2000km in his twenties. He tried eating dolphin meat raw to determine the amount of energy it’d give him if he’d ever have no other choice but to eat raw dolphin meat. He apprenticed with the Eskimos, learning from them what to wear – loose but protective clothing to prevent sweat, observing how they never hurried.

- “Amundsen’s philosophy: You don’t wait until you’re in an unexpected storm to discover that you need more strength and endurance. You don’t wait until you’re shipwrecked to determine if you can eat raw dolphin. You don’t wait until you’re on the Antarctic journey to become a superb skier and dog handler. You prepare with intensity, all the time, so that when conditions turn against you, you can draw from a deep reservoir of strength. And equally, you prepare so that when conditions turn in your favor, you can strike hard.”

- Amundsen was extra-prepared going to the journey. Scott ran everything so close to his prediction such that if something fails, the whole plan was in great jeopardy.

- “A single detail aptly highlights the difference in their approaches: Scott brought one thermometer for a key altitude-measurement device, and he exploded in “an outburst of wrath and consequence” when it broke; Amundsen brought four such thermometers to cover for accidents.”

- Even their choice of dogs and mode of transportation were very different: Scott used ponies – which sweat and didn’t eat meat, while Amundsen researched his choice of dogs and figured that he might along way get rid of the underperforming ones and have it be energy for the good-performing ones.

- “Amundsen didn’t know precisely what lay ahead. He didn’t know the exact terrain, the altitude of the mountain passes, or all the barriers he might encounter. He and his team might get pounded by a series of unfortunate events. Yet he designed the entire journey to systematically reduce the role of big forces and chance events by vigorously embracing the possibility of those very same big forces and chance events. He presumed bad events might strike his team somewhere along the journey and he prepared for them, even developing contingency plans so that the team could go on should something unfortunate happen to him along the way. Scott left himself unprepared and complained in his journal about his bad luck. “Our luck in weather is preposterous,””

- “DIFFERENT BEHAVIORS, NOT DIFFERENT CIRCUMSTANCES: Amundsen and Scott achieved dramatically different outcomes not because they faced dramatically different circumstances. In the first 34 days of their respective expeditions, Amundsen and Scott had exactly the same ratio, 56 percent, of good days to bad days of weather.4 If they faced the same environment in the same year with the same goal, the causes of their respective success and failure simply cannot be the environment. They had divergent outcomes principally because they displayed very different behaviors.”

- “On the one hand, 10Xers understand that they face continuous uncertainty and that they cannot control, and cannot accurately predict, significant aspects of the world around them. On the other hand, 10Xers reject the idea that forces outside their control or chance events will determine their results; they accept full responsibility for their own fate. 10Xers then bring this idea to life by a triad of core behaviors: fanatic discipline, empirical creativity, and productive paranoia. Animating these three core behaviors is a central motivating force, Level 5 ambition. (See diagram “10X Leadership.”) These behavioral traits, which we introduce in the remainder of this chapter, correlate with achieving 10X results in chaotic and uncertain environments. Fanatic discipline keeps 10X enterprises on track, empirical creativity keeps them vibrant, productive paranoia keeps them alive, and Level 5 ambition provides inspired motivation.”

- “Discipline, in essence, is consistency of action—consistency with values, consistency with long-term goals, consistency with performance standards, consistency of method, consistency over time…

True discipline requires the independence of mind to reject pressures to conform in ways incompatible with values, performance standards, and long-term aspirations. For a 10Xer, the only legitimate form of discipline is self-discipline, having the inner will to do whatever it takes to create a great outcome, no matter how difficult.”” - “Social psychology research indicates that at times of uncertainty, most people look to other people—authority figures, peers, group norms—for their primary cues about how to proceed.16 10Xers, in contrast, do not look to conventional wisdom to set their course during times of uncertainty, nor do they primarily look to what other people do, or to what pundits and experts say they should do. They look primarily to empirical evidence.”

Conventional wisdom means relying on direct observation, examining evidence rather than relying on conventional wisdom or untested ideas. - 10x leaders differ from other successful leaders in their ability to always think – even in the best of circumstances, that things will go wrong, and be ready for it instead of making it paralyze you.

- It is better to invest in a company that has consistent performance of say an annual 20% growth consistently for 20 years, vs investing in another company that achieves the same growth rate of over 20years but is extremely volatile in its annual growth.

To have a 20 Mile March mentality, you need to have two bounds: lower where there is a threshold that you don’t go under but at the same time you have the patience not to go above it. - “If you deplete your resources, run yourself to exhaustion, and then get caught at the wrong moment by an external shock, you can be in serious trouble. By sticking with your 20 Mile March, you reduce the chances of getting crippled by a big, unexpected shock. Every 10X winner pulled further ahead of its less successful comparison company during turbulent times. Ferocious instability favors the 20 Mile Marchers. This is when they really shine.”

- “The case of Genentech under Levinson highlights two points. First, 20 Mile Marching can help you turn underachievement into superior achievement; so long as you stay alive and in the game, it’s never too late to start the march. Second, searching for—and even finding—the Next Big Thing does not in itself make a great company. Like a gifted but undisciplined athlete, Genentech had underperformed and disappointed, making good on its promise only once Levinson added fanatic discipline to the mix.”

- A good 20 Mile March has the following characteristics:

- Has an end-goal

- Milestones towards achieving that end goal and clear ways of measuring that performance.

- Imposes constraints and discipline from within

- Takes your own capabilities and your ability to achieve it.

- A company can adopt a 20 Mile March discipline even if it hasn’t had such discipline in earlier in history.

- “if we came out and said, “Innovation is bad,” we could justifiably be called stupid. But that isn’t our point; we’re not saying that innovation is unimportant. Every company in this study innovated. It’s just that the 10X winners innovated less than we would have expected relative to their industries and relative to their comparison cases; they were innovative enough to be successful but generally not the most innovative.We concluded that each environment has a level of “thresh old innovation” that you need to meet to be a contender in the game; some industries, such as airlines, have a low threshold, whereas other industries,such as biotechnology, command a high threshold. Companies that fail even to meet the innovation threshold cannot win. But—and this surprised us—once you’re above the threshold, especially in a highly turbulent environment, being more innovative doesn’t seem to matter very much”

- The book looks at Intel vs AMD in the early 70s as they were racing to come up with a fast chip. Intel had a mjaor problem on its hand: its memory chip was randomly losing information. Intel spent months trying to fix the issue – employees working 80hrs/week. Meanwhile AMD was ahead of Intel in innovation. Ultimately Intel won the race because “Intel Delivers”. Intel obsessed over manufacturing, delivery and scale. “we want to do one good job on engineering” and “sell it over and over again”.

- The book emphasizes the importance of experimenting in a way that won’t have catastrophic consequences on you but can lead to great discoveries. Once you get that discovery, you can bet big on it.

- The authors of the book maintain that 10xers do not have any special ability to predict the future. Rather than being paralyzed by life’s uncertainties or trying to analyze your way to the right answer, instead you should focus on finding empirical evidence by asking the following questions:

- How can we bullet our way to understanding?

- how can we fire a bullet on this?

- what does this bullet teach us?

- do we need to fire another bullet?

- do we have enough empirical validation to fire a cannonball?

- Eventually, there comes a time for you to fire a big cannonball and commit to a big bet or audacious objective, otherwise you’ll never do anything great.

- Bullet –> calibrate —> bullet –> recaliberate –>cannonball

When Steve Jobs was considering opening retail stores in the early 2000s, he recognized that he didn’t know how to do it. He reached out to the person who knew how do it best – the CEO of Gap, and lured him into Apple’s Board of Directors. He learned from him not to launch big, but instead to try one store first and only expand when it’s successful. Steve did that, the first launch was a failure, but he and his retail designer kept refining until they got it. After the successful launch of the first two stores, Apple rolled the stores with great consistency. - Apple’s success is the result of marriage of empirical creativity – Steve Jobs, and extreme discipline – Tim Cook, more so than breakthrough innovation per se.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple and hired Tim Cook, they ruthlessly cut all unnecessary costs and eliminated anything that is not needed. The expected employees to work hard. They looked at the success of the past – Personal Macintosh, and used it to launch the Power Mac and iMac. Apple saw an opportunity in the music industry, where MP3 players and Napster were quite popular among the young. They wanted to capitalize on that to increase the dominance of their digital hub strategy. - Productive Paranoia means that you manage for unexpectedly sudden and extremely bad events before they happen – think stock market crash of Feb 2020. You zoom in and out to identify to sense changing conditions and respond effectively. You build buffers before the bad events happen.

- Intel had a large reserve of cash relative to revenue – 40%. while this was inefficient 95% of the time, Intel did it for the 5% of the time to protect against black swan events – unforeseen extreme disruption of the current environment. The world is not stable, safe, predictable or safe. While the probability of successfully predicting a black swan event might be less than 1%, the probability of a black swan event happening at some point is close to a 100%, and that is why you build extra cushion long before the storm hits.

- When a calamitous event clobbers an industry or the overall economy, companies fall into three categories: they die, they fall behind or they pull ahead. The calamity doesn’t determine the category, each company does.

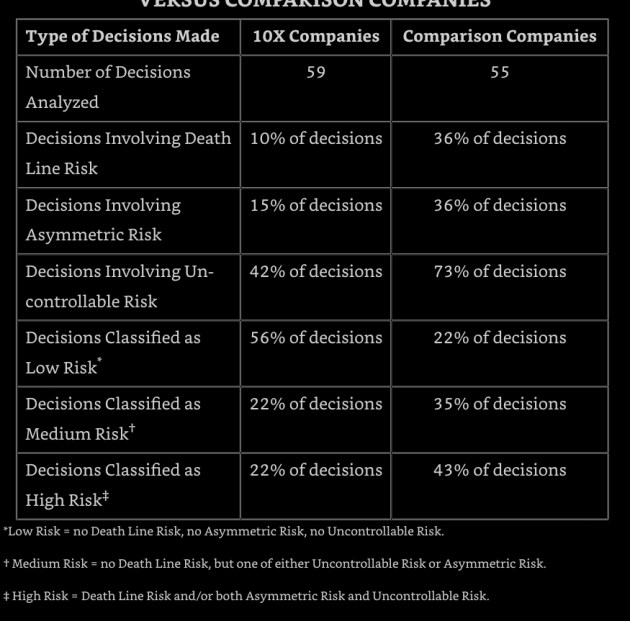

- There are three types of risks to be considered when making a decision: High Risk – those decision that if they fail can be catastrophic or extremely damaging, uncontrollable risks: related to factors that you cannot change, and asymmetric risk: where the risk of failure can be more damaging than the gains of success.

- “Sometimes acting too fast increases risk. Sometimes acting too slow increases risk. The critical question is, “How much time before your risk profile changes?” Do you have seconds? Minutes? Hours? Days? Weeks? Months? Years? Decades? The primary difficulty lies not in answering the question but in having the presence of mind to ask the question.”

- In practice, Zooming out of a situation looks like this:

- Sense a change

- Ask yourself “how much time do I have to act before my risk profile changes?”

- Assess with rigor if the new plans call for a change in plans, if yes, how.

- After that, Zoom In and focus on the execution of plans and objectives.

- Not all times in life are equal. We will all face moments in our life when the quality of our performance matters much more than other moments, moments that we can squeeze or surrender. 10xers prepare for these moments, recognize those moments, grab those moments, upend their lives in those moments, and deliver their best in those moments.

- “Now, you might be thinking, “OK, the primary finding here is to have a SMaC recipe.” But in fact, the existence of a recipe per se did not systematically distinguish the 10X companies from the comparison companies. Rather, the principal finding is how the 10X companies adhered to their recipes with fanatic discipline to a far greater degree than the comparisons, and how they carefully amended their recipes with empirical creativity and productive paranoia.”

- Change is not the most difficult part. Faro more difficult is figuring out what works, understanding why it works, grasping when to change and knowing when not to.

- The key to mediocrity is not the unwillingness to change but chronic inconsistency.

- How to know when to change a SMaC recipe? based on empirical creativity – fire bullets and see if they click, and based on productive paranoia: zoom out to perceive and assess a change in condition, then zoom in to implement amendments as needed.

- By the time a 25 year old engineer at MSFT sounded the alarm in 1994 about the internet and how MSFT wasn’t ready for it, Bill Gates already had a zoom out mechanism already in place, a “Think Week”. He spent that week learning about the internet, then came out and wrote to MSFT about his evolving views on the internet and how MSFT needs to seize the opportunity. He asked that the new operating system be internet-ready.

Having said that, MSFT did not change its other operating principles: incrementally improve, stay in the application world, build more OSes. - There is tension between change and consistency. When framers of the US constitution were building the constitution, they were faced with a profound question: How to build a constitution that will withstand the test of time, yet be flexible to accommodate unforeseen changes? The constitution cannot be too general so as not to have “teeth” but it also cannot be too rigid.

The solution was the amendments. They can only happen though is 2/3 of the senate and congress approve it and if the 3/4 of the individual states approve it. - In a great twist of irony, those who bring about the most significant change int he world, those who have the largest impact on economy and society, are themselves enormously consistent in their approach.

SMaC: stands for Specific, Methodical and Consistent. The more uncertain, fast-changing, and unforgiving the environment, the more SMaC you need to be. - Developing a SMaC and adhering to it requires three 10xers behavior: empirical creativity – to develop it, fanatic discipline – to stick to it, and productive paranoia – to zoom out and sense necessary changes.

- A lucky event is one that passes 3 tests: it happens independently of the actor’s actions, it has a big impact, and the element has some element of unpredictability.

- The book brings up the example of Ray Bourque who’s become world-class in Hockey but came from very humble beginnings. While he was a gifted physcial specimen, and he likely had superior skills even as a youngster, most players did. Bourque explains why he was an exception:

““Goals live on the other side of obstacles and challenges,” said Bourque. “Along the way, make no excuses and place no blame.”43 Bourque had luck in his journey, good and bad, but luck did not make Bourque into one of the greatest hockey players of all time. Now, you might be thinking, “But Bourque is an exception.” Precisely. The whole point is to become exceptional. Nietzsche famously wrote, “What does not kill me, makes me stronger.”44 We all get bad luck. The question is how to use that bad luck to make us stronger, to turn it into “one of the best things that ever happened,” to not let it become a psychological prison. And that’s precisely what 10Xers do.” - 10xers recognize that we swim in a sea of luck. They understand that we cannot cause, control and or predict luck, but by behaving in 10x ways, they make the most of the luck they get. there is an adage that says ” better be lucky than good”, and that is true if you just want to be good, but if you want to be much better than average, creating nothing but excpetional, then it’s far better to be great than lucky.

- “We sense a dangerous disease infecting our modern culture and eroding hope: an increasingly prevalent view that greatness owes more to circumstance, even luck, than to action and discipline—that what happens to us matters more than what we do. In games of chance, like a lottery or roulette, this view seems plausible. But taken as an entire philosophy, applied more broadly to human endeavor, it’s a deeply debilitating life perspective, one that we can’t imagine wanting to teach young people. Do we really believe that our actions count for little, that those who create something great are merely lucky, that our circumstances imprison us? Do we want to build a society and culture that encourage us to believe that we aren’t responsible for our choices and accountable for our performance? Our research evidence stands firmly against this view. This work began with the premise that most of what we face lies beyond our control, that life is uncertain and the future unknown. And as we wrote in Chapter 7, luck plays a role for everyone, both good luck and bad luck. But if one company becomes great while another in similar circumstances and with comparable luck does not, the root cause of why one becomes great and the other does not simply cannot be circumstance or luck. Indeed, if there’s one overarching message arising from more than six thousand years of corporate history across all our research—studies that employ comparisons of great versus good in similar circumstances—it would be this: greatness is not primarily a matter of circumstance; greatness is first and foremost a matter of conscious choice and discipline. The factors that determine whether or not a company becomes truly great, even in a chaotic and uncertain world, lie largely within the hands of its people. It is not mainly a matter of what happens to them but a matter of what they create, what they do, and how well they do it. This book and the three that precede it (Built to Last, Good to Great, and How the Mighty Fall) are looks into the question of what it takes to build an enduring great organization. As we conducted the 10X research, we simultaneously tested the concepts from the previous work, considering whether any of the key concepts from those works ceased to apply in highly uncertain and chaotic environments. The earlier concepts held up, and we are confident that the concepts from all four studies increase the odds of building a great company. But do they guarantee success? No, they don’t. Good research advances understanding but never provides the ultimate answer; we always have more to learn. And life offers no guarantees. It’s always possible that game-ending events and unbendable forces—disease, accident, brain injury, earthquake, tsunami, financial calamity, civil war, or any of a thousand other possible events—will subvert our strongest and most disciplined efforts. Still, we must act. When the moment comes—when we’re afraid, exhausted, or tempted—what choice do we make? Do we abandon our values? Do we give in? Do we accept average performance because that’s what most everyone else accepts? Do we capitulate to the pressure of the moment? Do we give up on our dreams when we’ve been slammed by brutal facts? The greatest leaders we’ve studied throughout all our research cared as much about values as victory, as much about purpose as profit, as much about being useful as being successful. Their drive and standards are ultimately internal, rising from somewhere deep inside. We are not imprisoned by our circumstances. We are not imprisoned by the luck we get or the inherent unfairness of life. We are not imprisoned by crushing setbacks, self-inflicted mistakes or our past success. We are not imprisoned by the times in which we live, by the number of hours in a day or even the number of hours we’re granted in our very short lives. In the end, we can control only a tiny sliver of what happens to us. But even so, we are free to choose, free to become great by choice.””Q: What are the implications for innovation-driven economies of your finding that 10X cases didn’t always out-innovate comparison companies? Our research suggests that treating innovation alone as the silver bullet for achieving a competitive advantage would be naïve and unwise. We conclude that 10X success requires the ability to scale innovation with great consistency, by blending creativity and discipline to build organizations that turn innovation into sustained great performance. This is the Intel story. It’s also the Southwest story, the Microsoft story, the Amgen story, the Stryker story, the Biomet story, the Progressive story, the story of the resurgence of Genentech under Levinson, and even the Apple story during its best years. If an enterprise—whether a company or a nation—retains its creativity yet loses discipline, increases pioneering innovation yet forgets how to multiply that innovation at scale (and at minimum cost), our research suggests that enterprise will be at risk.”

- “Q: My world feels fairly stable right now; does this apply to me? Remember a lesson from Chapter 5: it’s what you do before the storm comes that most determines how well you’ll do when the storm comes. Those who fail to plan and prepare for instability, disruption, and chaos in advance tend to suffer more when their environments shift from stability to turbulence.”

- “Q: How did the 2008 financial meltdown affect your thinking for this study? It served only to reinforce the relevance of the study question. Very few people predicted the 2008 financial crisis. The next Great Disruption will come, and the next one after that, and the next one after that, forever. We cannot know with certainty what they’ll be or when they’ll come, but we can know with certainty that they will come. Q: Are you more or less optimistic and hopeful after conducting this study? We’re much more optimistic and hopeful. More than any of our prior research, this study shows that whether we prevail or fail, endure or die, depends more upon what we do than on what the world does to us. We take particular solace from the fact that every 10Xer made mistakes, even some very big mistakes, yet was able to self-correct, survive, and build greatness.”